CPAESS and NOAA OAP: Partnering to understand changes in ocean chemistry

Our ocean acts like a great sponge for absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. It absorbs roughly 30% of this CO2 and the additional uptake changes seawater chemistry, increasing its acidity. This process called ocean acidification can impact marine life and people who depend on healthy ecosystems.

Kaity Goldsmith in the laboratory. She is a CPAESS program specialist with the NOAA Ocean Acidification Program (OAP). Photo credit: NOAA.

It’s this process that consumes – and fascinates – Kaity Goldsmith. A program specialist with the UCAR Cooperative Programs for the Advancement of Earth System Science (CPAESS), Goldsmith oversees a research portfolio of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Ocean Acidification Program (OAP) that employs four other CPAESS staff who work with NOAA OAP.

“Our ocean’s chemistry is changing,” says Goldsmith. “Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution when humans started burning fossil fuels like coal and oil, it has had the unintended side effect of increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.”

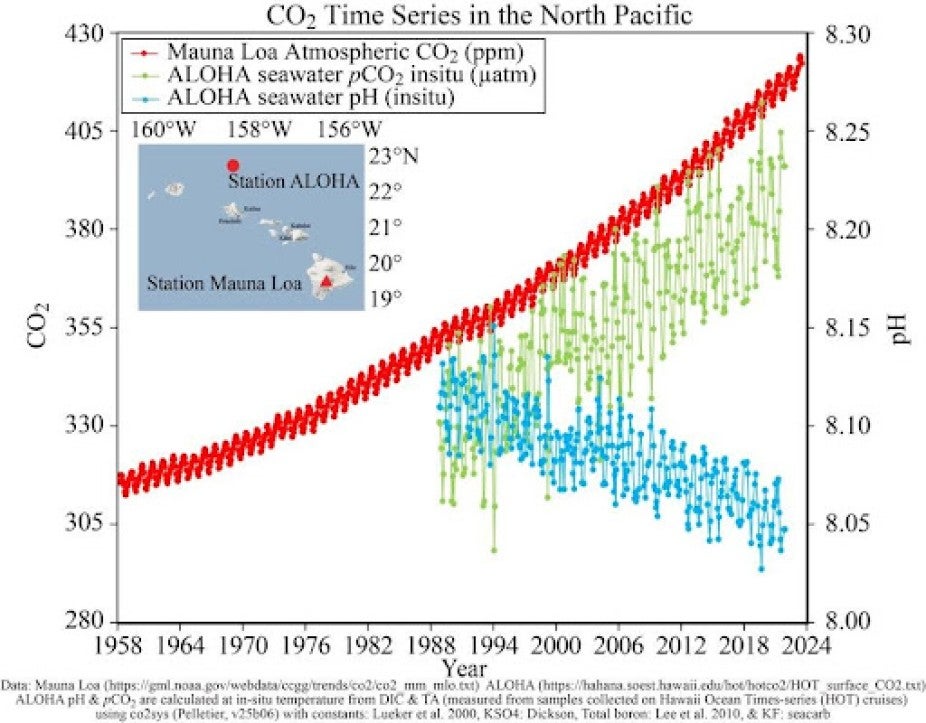

Our ocean absorbs those emissions, making conditions more difficult for a number of ocean species to perform certain life functions. Observations from the Hawaii Carbon Dioxide Time Series show an uptick in the amount of dissolved CO2 in the surface waters of the ocean.

Graph showing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) increase in the North Pacific Ocean since the 1950s and seawater carbonate change since the 1980s. Graphic credit: Hawaii Carbon Dioxide Time Series, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

Recent research indicates that under high CO2 emission scenarios, the ocean’s ability to absorb CO2 in the future may diminish and ocean chemistry changes may intensify.

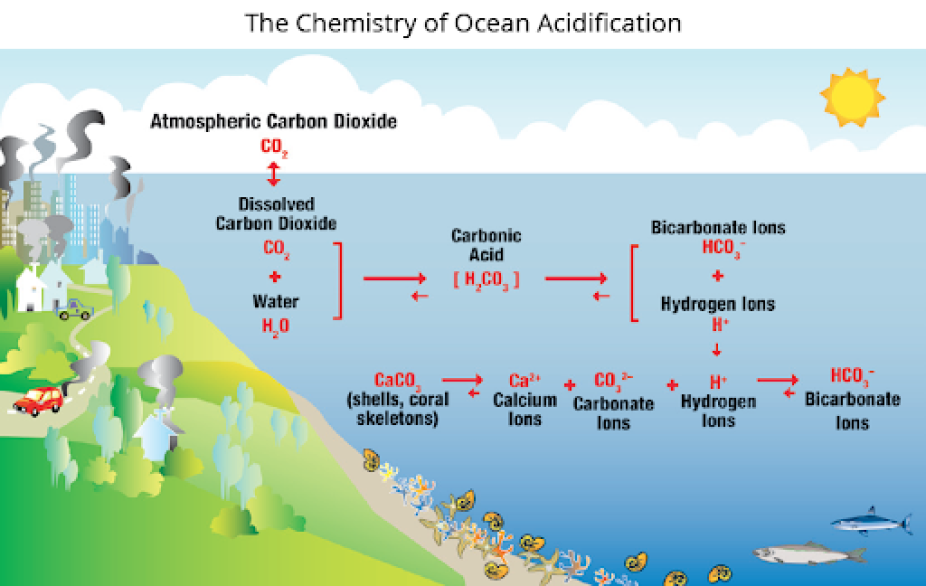

However, it isn’t simply about CO2 absorption.

“There are a number of different chemical reactions that occur with the deposition of carbon dioxide,” says Goldsmith. “This process triggers an increase in hydrogen ions that act like free agents in the ocean.” So, pH, where H indicates hydrogen ions, is another indicator of chemical changes in the ocean. “While the ocean itself isn’t acidic, the ocean is increasing in acidity,” she notes.

The free agent hydrogen ions are central to another reaction that reduces available calcium carbonate, a building block mineral needed by corals, mussels, lobsters, and other organisms that form shells. Hydrogen ions compete with calcium to bond to carbonate, which reduces the amount of this important mineral in seawater. Inadequate calcium carbonate can weaken shells and slow growth rates.

“Some marine life expends more energy acquiring this important building block where ocean acidification occurs,” says Goldsmith. “Many other species experience impacts to a number of other physiological processes at a variety of life stages while at the same time others, like algae and seaweeds, can actually grow more quickly due to higher rates of photosynthesis,” she said.

The chemistry of ocean acidification showing the chemical reactions that occur as seawater acidifies. Graphic credit: Northeast Coastal Acidification Network.

There are many different drivers of climate change. “Scientists are observing that ocean acidification can interact with other climate-related stressors,” she notes. As oceans warm, it’s important to conduct research that looks at species under acidified and warmer waters. The interaction between ocean acidification and warming in different places could exacerbate, cancel out or ameliorate the effects on different species.

“We need to understand the complex dynamics at play in the process of acidification if we are going to understand what the oceans will look like in the future,” says Goldsmith.

Congress understood the urgency to fund research to study the processes involved in ocean acidification that could lead to methods of adaptation or mitigation. By authorizing the Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Act in 2009, Congress took the first step in establishing the Ocean Acidification Program within NOAA.